Archaic Michigan Maps

One the many research rabbit holes I fell down while preparing Wild and Woolly Days was old maps of the Upper Peninsula. Not just 1880-1920 maps, but really old maps. They are full of imaginary islands, odd names, charming little drawings. What’s more, many of these maps have been put online and are easily accessible. Let’s take a look at some of them.

Finding the earliest map of “Michigan” is easier than some other states, because Michigan’s borders are determined by the Great Lakes. Look for the largest lakes on any North American map and you will find Michigan… more or less.

While early mapmakers may have had vague idea that the Great Lakes existed, they some pretty funky ideas on just what they were supposed to look like. Many maps are online and easily viewed (and giggled over). Maybe they were genuinely doing their best, based on other people accounts. Maybe they were just making stuff up. Maybe both.

Take a look at this map from 1600 (called the Molineaux-Wright map). There is a body of water there, where the Great Lakes should be. Most likely, it supposed to be Hudson’s Bay, but it could be Lake Ontario too, couldn’t it?

As more and more explorers came back to Europe with their rumors and stories, mapmakers revised their maps. (Etienne Brulé is said to have been the first European to see the Great Lakes, sometime between 1611 and 1615). In 1650s Nicolas Sanson, royal geographer to the kings of France, prepared a map of North America, part of which is shown below.

The thumb is enormous, the northern lower peninsula is far too narrow, and Lake Michigan (or “Lac des Puans) veers off in a westerly squiggle. The U.P. is there, though, even it’s a weird, chicken-finger shape (the “velle” is part of Novelle France).

By the 1670s reports from French explorers and Jesuit missionaries (Father Marquette being the most famous) were sending far more detailed information back to France, and far more accurate maps were being drawn.

So we went from this:

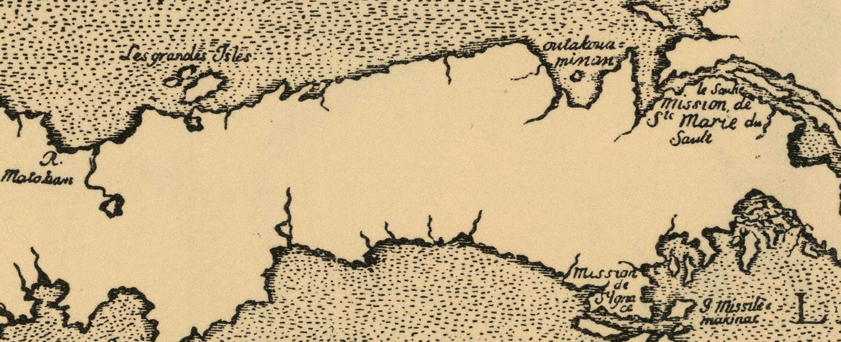

To this beauty, attributed to Jesuits Claude Allouez and Claude Dablon, circa 1668:

This is pretty cool. Look closer:

It has Grand Island, the Soo, St. Ignace, Mackinac Island, and even the first mention of the name Tahquamenon (it’s the island in the top, right corner, spelled “outakwaminon”). The Upper Peninsula was placed to be well represented in future maps.

The lower peninsula did not far quite as well. The 1714 Dutch map (below, left) has it be small and shriveled, while the 1716 German version on the right went in the opposite direction, favoring a bloated appearance.

I don’t know what’s going on with this English map (below) of 1719. Isle Royale has a mysterious twin. The lower peninsula has a mountain range, and who knows what’s going on with Green Bay. The English sure didn’t. That was French country.

So now we are in the 18th century. Both the French and English maintained forts around the Straits of Mackinac during this time. As they became familiar with the area, mapmakers began to add in more and more details. They didn’t always get the details right, but it’s a start.

Take this French map from 1775 (below) when the Revolutionary War was just kicking off. We’ve got Point de Kiaonan (Keweenaw), the grand Island, Tokou a minan (in the wrong spot), Grand Marais, Grand Sable, Whitefish Point, Point Iroquois, Isle au Castors (Beaver Island) which is the wrong size in the wrong spot and Ance de Kionan, which must be L’Anse.

After the Revolutionary War, Britain gave up most of the Great Lakes to the new United States, which formed it together into what was called the Northwest Territory.

The map below, produced by Gilbert Imlay, appeared in 1796 “drawn from the best authorities.”

Ick. Maybe he should have consulted with the Jesuits.

Things began to look up in 1820, when Lewis Cass, governor of Michigan Territory, led an expedition through Lake Superior, trying to find the Mississippi River. Although they mostly ignored the interior of the Upper Peninsula, they did note the location of many rivers (naming many of them). Michigan maps took a giant leap forward, as seen here in this 1822 map of the eastern U.P.

In 1837 Michigan Territory had graduated into being the State of Michigan. Now it was ready to really and truly map itself, and surveyors poured into the woods, once and for all setting us up for the familiar state outlines we all now and love.

The maps I’ve highlighted here are only a fraction of the weird and wacky ones available. If you are interested in more, check out the following websites: